On Security Assumptions Underpinning Recent Schnorr Threshold Schemes

Chelsea Komlo | August 5, 2022

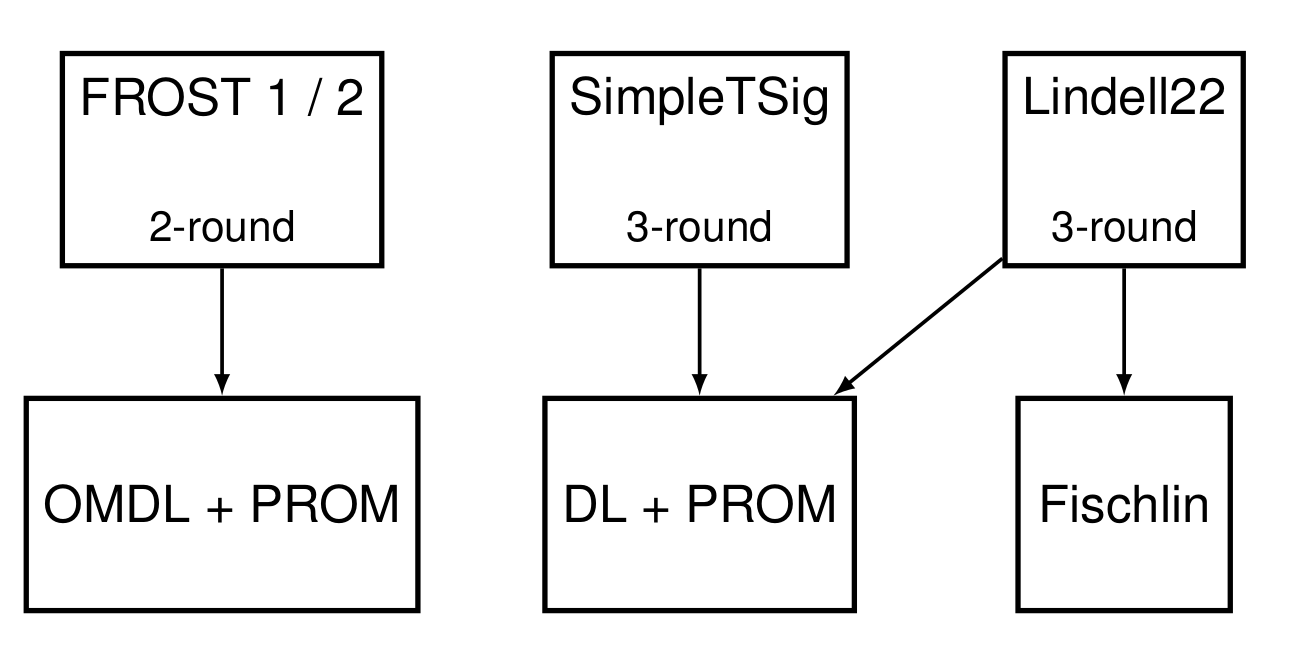

In this post, we discuss differences in the security assumptions underpinning four Schnorr threshold signature schemes. In particular, we will review the two-round FROST signing protocol by Komlo and Goldberg1 that we refer to as FROST1, as well as an optimized variant FROST2 by Crites, Komlo, and Maller2. We refer to these schemes in conjunction as FROST 1/2. We contrast these schemes with two three-round signing protocols: SimpleTSig, also by Crites, Komlo, and Maller2, as well as the three-round scheme by Lindell3, which we call Lindell22.

TLDR.

- FROST1/2 requires One-More Discrete Logarithm (OMDL) and Programmable Random Oracle Model (PROM) assumptions.

- SimpleTSig can be proven using only discrete logarithm (DLP) and PROM assumptions.

- Lindell22 can be proven using only DLP+PROM. The protocol employs the Fischlin Transform4 in lieu of Schnorr signatures for proofs of knowledge.

These assumptions refer only to the security of threshold signing and not to the distributed key generation process. Thanks to Elizabeth Crites and Mary Maller for feedback on this post.

Let's dig more into the details now.

Part One: What are security models, and why do they matter?

Security models are a useful tool to allow for proving cryptography schemes while also indicating potential assumptions which may or may not hold in practice. Each security model encodes certain assumptions such as an adversary's capabilities, the ability to perfectly simulate certain functionality, or the properties of the underlying mathematical assumptions. For example:

- The Standard Model. The adversary is limited only by time and computational power.

- The Random Oracle Model (ROM). Assumes outputs from a hash function are indistinguishable from random values.

- The Programmable Random Oracle Mode (PROM). Allows the random oracle to be programmed by the execution environment (which runs the adversary and simulates responses to the adversary's oracle queries), with the restriction that the programming must be indistinguishable from all other truly random responses.

Part Two: What are security assumptions, and why do they matter?

A security assumption simply states the assumed hardness to an adversary of some particular computational problem. For example:

-

Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP). Considered to be a "standard assumption" in cryptography. The problem is simple: given some challenge that is in a group where is a generator of , output the discrete logarithm relation between and , where .

-

One More Discrete Logarithm Assumption (OMDL). OMDL was first introduced by Bellare et al.5 and proven secure6, and can be as follows: given discrete logarithm challenges and access to a discrete logarithm solution oracle which can be queried up to times, the challenge is to output discrete logarithm solutions for all .

While perhaps not considered a "standard" assumption in the same way that plain Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) or other problems that reduce to simply a single discrete logarithm assumption, OMDL underpins the security of many cryptographic schemes in theory and in practice, such as blind signatures.

- Knowledge of Exponent Assumption (KEA). KEA is a white-box assumption, and is not falsifiable (thus a stronger assumption than what we have reviewed thus far). KEA says that for an adversary given a generator of a group and random element such that for a random x, then if the adversary outputs a tuple such that , then there exists an extractor that will output . Informally, this means that the only way for the adversary to produce is by exponentiating each element in the tuple with the value , thereby demonstrating the adversary's knowledge of (as opposed to choosing random elements in ).

If you would like more context on how these assumptions are used to prove the security a cryptographic scheme, we give more context later in this post.

Part Three: I thought we were supposed to be talking about Schnorr threshold schemes...

Yes, we are! Finally getting to that.

The reason we wanted to write this post is because there has been some debate about the security of two-round Schnorr threshold signature schemes (FROST1/2) and how they compare to less efficient three-round Schnorr threshold signature schemes. We'll review these schemes now, and clarify their resulting security next.

FROST1 was introduced by Komlo and Goldberg in 20201. In that work, they did two things. They introduced 1) a Distributed Key Generation (DKG) protocol that is a minor improvement upon the Pedersen DKG7 that we will call PedPop, as well as 2) a novel two-round threshold signing protocol that is secure against ROS attacks8 that we refer to as FROST1.

FROST2 is an optimized variant of FROST1 by introduced by Crites, Komlo, and Maller in 20212, and reduces the number of exponentiations required for signing operations and verification from linear in the number of signers to constant.

SimpleTSig is a three-round threshold signature scheme also introduced by Crites, Komlo, and Maller2, and is the threshold analogue of a three-round multisignature scheme called SimpleMuSig, presented in the same work2.

Lindell22 is a three-round threshold signing protocol introduced by Lindell in 20223.

We next show that for threshold signing, SimpleTSig and Lindell22 require the weakest assumptions of all of these schemes. FROST1/2 requires sightly stronger assumptions due to OMDL. However, as mentioned before, OMDL underpins many existing cryptosystems such as blind signatures.

We split this analysis into two parts, that of 1) key generation, and 2) signing. The reason for this split is because the key generation mechanism can be viewed as independent to signing, so long as it produces the expected secret and public key material required for signing operations. Hence, the security assumptions required by a certain key generation are imposed on a scheme only if that particular key generation mechanism is used.

Part Four: What assumptions underpin various key generation protocols that could be used by FROST1/2, SimpleTSig, or Lindell22?

We now describe three different key generation mechanisms, all of which can be used in conjunction with any of the threshold signature schemes described in part four. Note that this list is not exhaustive.

[Standard Model] Trusted key generation. In this setting, a trusted dealer can simply generate all key material and distribute it to each player via Shamir's secret sharing. Shamir's secret sharing is information-theoretically secure, but if Verifiable Secret Sharing (VSS) is used then the discrete logarithm assumption is required. VSS is generally helpful as it allows each participant to ensure that its share is consistent with other players. In each setting however, the dealer is trusted to perform key generation honestly and delete key material after. This variant is described more in the FROST CFRG draft in Appendix B.

[Standard Model] Pedersen. The security of the Pedersen DKG when used as key generation for FROST1, FROST2, SimpleTSig, or Lindell22 relies on at least half of the participants being honest and the underlying signature scheme being secure.

[KEA+PROM] PedPop. An efficient two-round DKG introduced by Komlo and Goldberg along with FROST1. PedPop is simply Pedersen DKG, with the additional step where each participant additionally publishes a Schnorr signature during the first round to prove knowledge of their secret key material. This extra step ensures that security holds given any threshold of honest parties. The security of PedPop when used as key generation for FROST2 and SimpleTSig was demonstrated2. Note that KEA is required for the environment to extract the adversary's secret keys in the proof of security; alternatively, the Fischlin transform could be used in lieu of Schnorr as the proof of possession (and so would be only in the PROM). See further discussion in Part 9.

[Standard Model] Gennaro et al. A three-round DKG that is secure in the standard model.

Part Five: Which assumptions does two-round threshold signing protocol FROST1/2 rely on?

FROST1/2 signing can be proven using:

- One-More Discrete Logarithm Assumption (OMDL)

- Programmable Random Oracle Model (PROM)

By reducing to OMDL, the environment does not need to rely on extracting secret information from the adversary during its simulation of signing; the adversary is simply required to output a valid forgery. The use of two nonces and the randomizing factor in FROST allows for a true reduction to OMDL, unlike prior related multisignature schemes that had subtle flaws in their attempt to an OMDL reduction9,

The proof for FROST11 required a heuristic assumption and so could not prove these properties directly. The proof for FROST22 provides a direct proof for FROST2 with PedPop as the key generation protocol. Proofs for FROST1 and FROST2 in a recent paper by Bellare, Tessaro, and Zhu10 employ an abstraction of key generation, and so demonstrate a direct reduction to PROM+OMDL.

Part Six: Which assumptions does three-round SimpleTSig signing rely on?

SimpleTSig signing can be proven using:

- Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP)

- PROM

The reason why SimpleTSig can be proven in ROM+DLP is because it relies upon a commit-open-sign protocol flow. Similarly to FROST 1/2, the environment does not need to extract secret values from the adversary during its simulation of signing; it simply requires that the adversary output a valid forgery at the end of the protocol.

Part Seven: Which assumptions does three-round Lindell22 signing rely on?

Lindell22 signing can be proven using:

- DLP

- PROM

Unlike FROST1/2 and SimpleTSig, Lindell22 employs Schnorr signatures at intermediate steps throughout the signing protocol so that participants can prove possession of their nonces. The proof of security requires the environment to extract the adversary's nonces in order to demonstrate the reduction to DLP. While employing Schnorr signatures is sufficient to perfectly simulate an idealized zero-knowledge and commitment functionality, Schnorr signatures are not sufficient for the environment to perform this extraction step.

Hence, Lindell22 must instead employ the Fischlin Transform in lieu of employing Schnorr signatures for the proof to go through in the PROM. Doing so has a non-zero impact on the performance and complexity of the protocol. See further discussion below on this topic.

Part Eight. I'm confused about why Fischlin/KEA are even required.

This is going to be dense, so hang on :)

In summary, the Fischlin Transform requires a change to the actual protocol so that the prover brute-forces to find a weak hash function output where the least significant bits are zero. Why is this transform necessary? In summary, it ensures that in the proof of security, the environment is able to extract the necessary secret information from the adversary for the proof to go through.

KEA simply defines an extractor that is assumed to be able to extract the correct values, given the constraints described above. Hence, this assumption is non-falsifiable and therefore considered a strong assumption.

Notably, KEA and Fischlin are often interchangable for protocols that require online extraction for proofs of possession. Lindell22 employs the Fischlin Transform (and hence is in the PROM), but could easily instead employ KEA. The proof for PedPop2 assumes KEA, but alternatively, could use Fischlin.

Forking+rewinding is how the unforgeability of Schnorr signatures is proven to reduce to the hardness of discrete log in the programmable ROM, when Fiat-Shamir is employed. We describe in more detail this reduction at the end of this post. However, while the proof of unforgeability for Schnorr signatures incurs acceptable tightness loss when forking+rewinding is used, the same is not true when Schnorr signatures are employed as proofs of possession (PoP) and the environment must extract secret information from the adversary, as is the case in PedPop and Lindell22. In the extractability case, the tightness loss incurred is instead exponential. Hence why in the PoP setting where extractability is required, either KEA or Fischlin must instead be employed.

The Fischlin Transform provides an alternative to forking+rewinding, so that the environment can similarly extract secret information in an online manner, hence allowing for a tight(er) proof. Sounds too good to be true? It is, a bit. The Fischlin Transform requires the prover to brute-force finding a challenge where the least significant bits of the challenge must be all zeros. Hence, since the prover is unlikely to find this challenge immediately, it must make many challenge queries, therefore allowing the environment to extract secret values, similarly to the forking+rewinding case. However, unsurprisingly, doing so is expensive for reasonable security parameters.

Part Nine: This post is really long. What should I take away from all of this?

Let's summarize the key takeaways.

- Two-round threshold signing protocols FROST 1 and FROST2 rely on the programmable Random Oracle Model (PROM) and One-More Discrete Logarithm (OMDL) assumptions.

- Three-round threshold signing protocol SimpleTSig relies on PROM + DL.

- Three-round threshold signing protocol Lindell22 relies on PROM + DL. The Fischlin Transform imposes some performance costs.

Thanks, and happy threshold signing!

More on proving the security of cryptographic schemes

Similar to demonstrating that a problem is in NP for complexity theory by reducing the problem to another known NP problem, in cryptography, we use reductions to hard mathematical problems to demonstrate that breaking a cryptography scheme is as hard as breaking some known-to-be-hard mathematical problem. For example, we might say that "an adversary wishing to compromise the security of a key-exchange protocol must solve for the discrete logarithm of a value, where the most efficient way to do it is by brute force, which takes X computational power over Y number of years." We model the adversary as a black-box randomized algorithm, which is run by the execution environment, outputting some value at the end, resulting in either a win or fail for the adversary. We can then provide a lower bound on how long it would take an adversary to eventually win (e.g., solve for an unknown discrete log), and determine parameters for the security.

Showing this reduction can be done a number of ways, but there are two proof techniques that are considered to be best practices in cryptography.

- Game-based proofs

- Simulation-based proofs.

Game-based proofs demonstrate that an adversary that wins in some game A can be used as a subroutine by another adversary to win in a different game B. Using our key-exchange example, we could show that an adversary that wins in a game against the key-exchange scheme could be used as a subroutine by another adversary to win in a game against the discrete logarithm problem. By a game, we simply mean some program that initializes an adversary, simulates oracle queries to it, and at the end determines if the adversary has successfully completed its attack.

Simulation-based proofs instead rely on proving that some function in the "real world" is indistinguishable to that function in the "ideal world." For example, we could call an encryption secure if an adversary that learns the output of some ciphertext of a real message (real world) obtains no more information than an adversary that learns a ciphertext of garbage (ideal world). The adversary is allowed to interact with the environment, receiving outputs representing the real world and the ideal world. We say the scheme is secure if the adversary successfully distinguishes between the two with negligible probability.

More on the reduction of Schnorr signatures to DLP

Above, we talked about proving the security of Schnorr signatures as the result of Fiat-Shamir by reducing to the hardness of DLP. We give this reduction step-by-step now:

- The environment is given as the challenge without knowing the secret key, and must simulate signing to an adversary, whose goal is to compute a forgery.

- When the adversary successfully produces a forgery (with some probability), the environment then forks its state, and then re-runs the adversary. The adversary again will produce a second forgery, outputting the following two forgeries to the environment.

- In the above, is the commitment (and importantly, is the same in the two tuples).

- is the challenge the adversary obtains from the challenge oracle (the random oracle H that the environment simulates) before the adversary is forked, and is the challenge after the adverary is forked, where importantly .

- is the adversary's forgery with respect to before the fork, and is the adversary's forgery with respect to after the fork.

- The environment can then extract simply by deriving .